You can take advantage of these savings both online and in our downtown Los Angeles store on Quilting Day, this Monday, March 19, and for an additional two days on our website only, at www.LowPriceFabric.com.

You can take advantage of these savings both online and in our downtown Los Angeles store on Quilting Day, this Monday, March 19, and for an additional two days on our website only, at www.LowPriceFabric.com.Now for a little story about Batik...

Humble Beginnings:

The word 'Batik' is thought to have come from the Javanese amba ('to write') and titik ('dot' or 'point'). The art form predates written Javanese records, and is thought by some to be a native tradition. Commonly, a mixture of beeswax and paraffin are used to create the resist area of a design. The beeswax holds the design to the cloth, and the paraffin has a tendency to crack, which is a stylization characteristic of batik. Here is an example of the spiderweb effect created by the cracked wax:

The word 'Batik' is thought to have come from the Javanese amba ('to write') and titik ('dot' or 'point'). The art form predates written Javanese records, and is thought by some to be a native tradition. Commonly, a mixture of beeswax and paraffin are used to create the resist area of a design. The beeswax holds the design to the cloth, and the paraffin has a tendency to crack, which is a stylization characteristic of batik. Here is an example of the spiderweb effect created by the cracked wax: This is a sneak peek at one of our new swimwear fabrics, available soon, in a print made to look like batik. Although it is not a real batik, it illustrates very well the crackled look that is characteristic of many batiks.

This is a sneak peek at one of our new swimwear fabrics, available soon, in a print made to look like batik. Although it is not a real batik, it illustrates very well the crackled look that is characteristic of many batiks.There are two main batik-making techniques:

The first, original type and method of batik, is called batik tulis, or written batik, and entails drawing a design freehand onto the cloth. It is a very time consuming method and was originally done mostly by women. Batik tulis is made using a wooden or bamboo handled tool with a tiny metal reservoir, and out of it the wax seeps, through a very tiny spout. This needle-like pen is called a canting (pronounced "chonting"), and looks like this:

Today, the batik tulis method is still used for designs of a freehand nature. Here is a picture from my last trip to Bali, where we visited a batiker replicating this floral sarong. You can see how the untreated cloth is stretched above the template and then the outline is "traced" in wax onto the blank sheet:

Today, the batik tulis method is still used for designs of a freehand nature. Here is a picture from my last trip to Bali, where we visited a batiker replicating this floral sarong. You can see how the untreated cloth is stretched above the template and then the outline is "traced" in wax onto the blank sheet:

Here, after the wax has been applied and dries, dyes are painted on the cloth, into the wax-segregated areas of the motif:

After the dye has been placed, the cloth is then placed in the sun. One batiker told me (and I'm sure this depends on the types of dye used) that the brightness of the sun dictates the intensity of the finished color. Interesting, right?

Here is an example of some exquisite silk batik tulis that I bought in Bali, made here into a beautiful wedding gown:

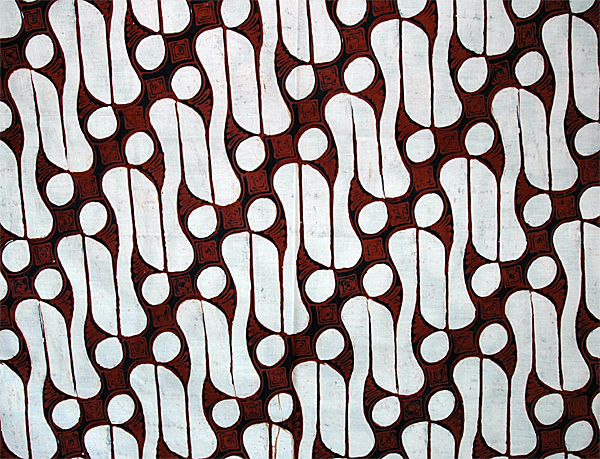

The secondary method, batik cap (pronounced "chop"), or stamped batik using copper blocks, was developed much later, in the 20th century, when production facilities faced a need to mass produce the detailed designs that would take ages to turn out using the traditional canting. Due to the labor intensive nature of this technique, batik cap was mostly done by men. Batik cap has a repetitive nature to the print. The batiks that we have just added at www.LowPriceFabric.com have all been made in this stamped manner. Here is an example; one of our many new additions:

The secondary method, batik cap (pronounced "chop"), or stamped batik using copper blocks, was developed much later, in the 20th century, when production facilities faced a need to mass produce the detailed designs that would take ages to turn out using the traditional canting. Due to the labor intensive nature of this technique, batik cap was mostly done by men. Batik cap has a repetitive nature to the print. The batiks that we have just added at www.LowPriceFabric.com have all been made in this stamped manner. Here is an example; one of our many new additions:

This material started out as a plain white or natural colored cloth. First, the light floral pattern you see within the design was stamped in wax. Next, the cloth was tie dyed, if you will, a pale, mottled blue/purple. The color was processed, rinsed, and then the wax removed, either by washing in hot water or by ironing between sheets of newspaper. Next, the cloth was stamped with wax again, this time in the volcano and house pattern. Then, dyed again in the same colors/manner as before, but this time salt is thrown at the cloth, creating the "fizzy" texture within the color. The dye is processed, rinsed, and then the wax removed again. This is what you call a double-process batik. The more processes it goes through, the more expensive the finished material will be. Some batiks have as many as three or four processes, or "layers," to the design.

This is what the cap, or batik stamp, looks like, made from sculpted copper. These stamps are masterpieces in themselves, and a new one (often custom made) will come with a high price tag of at least a couple hundred dollars. That is why batik stamps are often passed down and around, and it isn't uncommon to find them for sale second hand. The craftsmen who create these stamps have a career entirely in itself. The stamps are dipped in a reservoir of hot wax kept over low heat, and applied to the cloth in a block printing method, at just the right temperature:

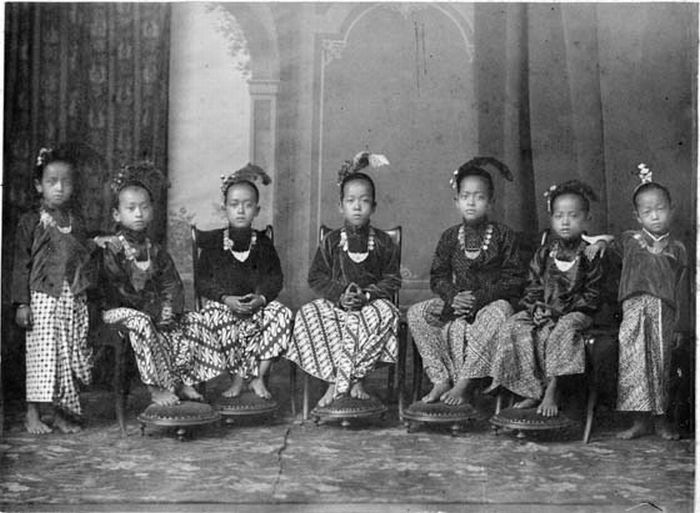

Other than the two methods by which it is produced, batik can be further sub-categorized by the style and design motif itself. To keep this from becoming a full on dissertation, I'll show you just one; my favorite, unmistakable pattern is Parang Rusak, or 'broken knife'. This style of batik pattern was originally reserved for royalty, for in historic times, ordinances were passed in the ruling centers of Java dedicating certain batik patterns as 'only wearable by members of certain status or relation to the sultan.' The differences in rank between members of the sultans' families and high officials could be easily determined by the batik pattern one wore. Commoners were expressly forbidden to wear these designs:

I thoroughly enjoy seeing such a traditional pattern and textile show up in modern fashion. Here are two images of Parang Rusak batik popping up in the western fashion scene:

I thoroughly enjoy seeing such a traditional pattern and textile show up in modern fashion. Here are two images of Parang Rusak batik popping up in the western fashion scene: Here, Jessica Alba arrives at a charity event in a very familiar print:

Here, Jessica Alba arrives at a charity event in a very familiar print:

Another common use for batik in the United States is for quilting. Many quilters enjoy mixing in a few batik quarters here and there, or some will even do a full quilt entirely of batik, featuring some sort of rainbow spectrum gradation. Just google images for 'batik quilt' and you'll turn up dozens of examples/ideas. Our selection of cotton batiks would be perfect for quilting, as we have shades of pink, orange, yellow, green, turquoise, blue, purple, and black:

Given the age and history of the art form, batik has certainly become the traditional cloth of the Indonesian people. It is worn for temple and ceremony events, used in most hotels and tourist attractions, placed in the home, and often salvaged and sewn up into patchwork blankets. And now, flight attendant uniforms on most of Southeast Asia's major airlines feature a "batik" looking printed cloth to replicate the traditional textiles of the region. What makes batik so desirable and interesting is its beauty, and the fact that it's made by hand under very traditional methods, without the need for industrial machinery or equipment. The techniques of old are still very much alive, and you can see from my photographs that the words 'primitive' and 'modern' are interchangeable when it comes to batik factories! The batiks we are selling online have all been made by hand by the artisans of Bali, Indonesia and imported by Hoffman of California. It is most pleasing to me that through the sale of these batiks, we are supporting and advocating the awareness of such a rich, creative culture and traditional textile art. I love batik and I hope that your experience with these textiles will open one door that leads to another, and that you may continue exploring and discovering beautiful batik textiles.

Given the age and history of the art form, batik has certainly become the traditional cloth of the Indonesian people. It is worn for temple and ceremony events, used in most hotels and tourist attractions, placed in the home, and often salvaged and sewn up into patchwork blankets. And now, flight attendant uniforms on most of Southeast Asia's major airlines feature a "batik" looking printed cloth to replicate the traditional textiles of the region. What makes batik so desirable and interesting is its beauty, and the fact that it's made by hand under very traditional methods, without the need for industrial machinery or equipment. The techniques of old are still very much alive, and you can see from my photographs that the words 'primitive' and 'modern' are interchangeable when it comes to batik factories! The batiks we are selling online have all been made by hand by the artisans of Bali, Indonesia and imported by Hoffman of California. It is most pleasing to me that through the sale of these batiks, we are supporting and advocating the awareness of such a rich, creative culture and traditional textile art. I love batik and I hope that your experience with these textiles will open one door that leads to another, and that you may continue exploring and discovering beautiful batik textiles.

[…] you’re curious about the roots of Batik and how it is made you can read more about it here and […]

ReplyDelete